Advertisement

Advertisement

Analysis-After extraordinary rally, bonds’ fate now with bank stability and inflation

By:

By Yoruk Bahceli (Reuters) - Borrowing costs in some of the world's biggest economies end a volatile quarter eyeing their sharpest drops in years and more swings are likely until it is clear whether central banks will focus on financial stability or inflation.

By Yoruk Bahceli

(Reuters) – Borrowing costs in some of the world’s biggest economies end a volatile quarter eyeing their sharpest drops in years and more swings are likely until it is clear whether central banks will focus on financial stability or inflation.

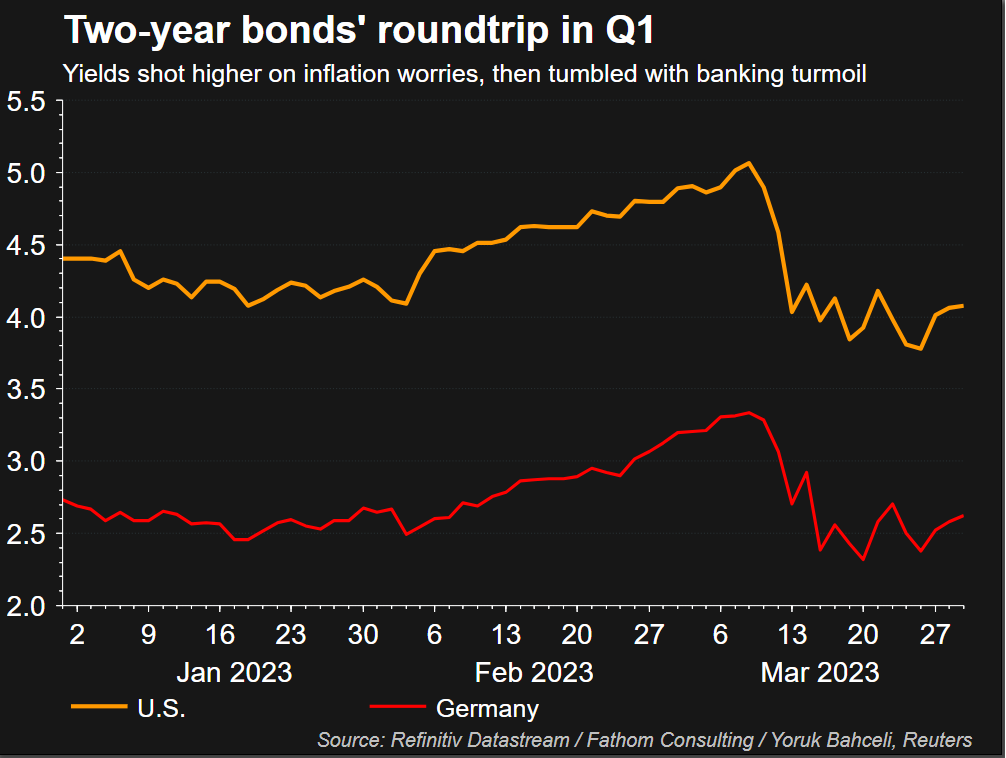

As of Thursday, two-year U.S. Treasury yields have slid 65 basis points (bps) in March, nearing their biggest monthly drop since January 2008, as U.S. lenders Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed and Credit Suisse was rescued.

Alongside that dash for safe havens was a rapid repricing of rate-hike bets as banking turmoil raised financial stability risks, fuelling the rally in government debt.

But coming so soon after markets had positioned for bigger U.S. rate hikes to tame inflation, bonds swung wildly. March’s sharp drop in two-year yields followed a 59 bps jump in February. A measure of volatility in the Treasury market hit its highest since 2008 in mid-March.

“That is not a normal move,” said Mike Riddell, senior fixed income portfolio manager at Allianz Global Investors, which manages 673 billion euros in assets.

Two-year U.S. yields are currently just above 4%, levels seen in early February before surging to over 5% shortly before SVB’s collapse on March 10, only to then fall sharply.

“You’re seeing 100 bps (yield) swings, one way and then the other in the space of six weeks, in terms of where the market thinks the Fed will have rates a year from now, which is the kind of volatility that you normally only ever see in the middle of a massive crisis,” Riddell said.

Markets now price around a 50% chance of a last, 25 bps Federal Reserve rate hike to 4.75%-5%, then cuts. In early March, they had priced rates peaking at 5.7%.

European Central Bank rates are seen peaking around 3.5%, from over 4% in early March.

The overall direction for bond yields was lower. Two-year Treasury yields are down 24 bps this quarter, their biggest quarterly drop since the 2020 COVID-19 crisis.

Germany’s two-year bond yield meanwhile has tumbled 35 bps in March, the second largest monthly drop since 2011. But it rose 5 bps during the quarter, another reflection of wild market swings.

Australian two-year yields dropped more than 50 bps in their biggest monthly fall since 2012. Japan’s 10-year yield fell the most since 2008 with a 19 bps drop.

What’s next?

What is next may depend on whether further banking stress leads to a credit crunch that helps tame inflation.

The likes of JPMorgan, BofA and Morgan Stanley, expect Treasury yields to end 2023 lower; others such as Goldman Sachs and BNP Paribas expect a rise.

“If we think that financial stability will be a less compelling, smaller problem than in the past two weeks, and price stability the bigger one … rates should not decline too much,” said Mauro Valle, head of fixed income at Generali Investments Partners.

Some are betting that banking woes have raised recession risks, a stark contrast to stock markets still up 1% this month despite a bank stocks rout.

Riddell at Allianz said the firm expected a recession ahead, meaning the Fed would likely lower rates “far below” 3% in a year to 18 months from now.

He favoured five to 10-year Treasuries, expecting a moderate recession could push yields another 100 bps lower but was underweight bonds in Europe, where inflation is stickier.

For others, markets have gone too far.

Craig Inches, head of rates and cash at Royal London Asset Management, said many of the same pressures that had made central banks uneasy about pausing rate hikes, such as high inflation, remained.

Indeed on Thursday, euro zone bond yields shot higher as German inflation data came in above forecast.

He took profits from a trade betting on shorter-dated yields falling faster than longer-dated ones and has reduced exposure to interest rate risk, expecting two more Fed hikes.

“If (central banks) do actually go on a pause or start cutting rates, then you open a real can of worms about what that is going to mean for inflation expectations if a massive systemic financial crisis does not materialise,” Inches said.

(Reporting by Yoruk Bahceli; Editing by Dhara Ranasinghe and Alison Williams)

About the Author

Reuterscontributor

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest international multimedia news provider reaching more than one billion people every day. Reuters provides trusted business, financial, national, and international news to professionals via Thomson Reuters desktops, the world's media organizations, and directly to consumers at Reuters.com and via Reuters TV. Learn more about Thomson Reuters products:

Latest news and analysis

Advertisement