Advertisement

Advertisement

Special Report-FTX’s Bankman-Fried begged for a rescue even as he revealed huge holes in firm’s books

By:

By Angus Berwick, Anirban Sen, Elizabeth Howcroft and Lawrence Delevingne

By Angus Berwick, Anirban Sen, Elizabeth Howcroft and Lawrence Delevingne

(Reuters) – As customers withdrew billions of dollars from crypto exchange FTX one frantic Sunday this month, founder Sam Bankman-Fried worked the phones in a futile bid to raise $7 billion in emergency funds.

Hunkered in his Bahamas apartment, Bankman-Fried toiled through the night, calling some of the world’s biggest investors, including Sequoia Capital, Apollo Global Management Inc and TPG Inc, according to three people with knowledge of the matter.

Sequoia was among investors that lined up only months before to pump money into Bankman-Fried’s empire. But not now. Sequoia was shocked at the amount of money Bankman-Fried needed to save FTX, according to the sources, while Apollo first asked for more information, only to later decline. Both firms and TPG declined to comment for this article.

In the end, the calls came to naught and FTX filed for bankruptcy on Nov. 11, leaving an estimated 1 million customers and other investors facing total losses in the billions of dollars. The collapse reverberated across the crypto world and sent bitcoin and other digital assets plummeting.

Some details of what happened at FTX have already emerged: Reuters reported Bankman-Fried secretly used $10 billion in customer funds to prop up his trading business, for instance, and that at least $1 billion of those deposits had vanished.

Now, a review of dozens of company documents and interviews with current and former executives and investors provide the most comprehensive picture so far of how Bankman-Fried, the 30-year-old son of Stanford University professors, became one of the richest men in the world in just a couple of years, then came crashing down.

The documents, reported here for the first time, include financial statements, business updates, company messages and letters to investors. They, along with the interviews, reveal that:

— In presentations to investors, some of the same assets appeared simultaneously on the balance sheets of FTX and of Bankman-Fried’s trading firm, Alameda Research – despite claims by FTX that Alameda operated independently.

— One of Bankman-Fried’s close aides tweaked FTX’s accounting software. This enabled Bankman-Fried to hide the transfer of customer money from FTX to Alameda. A screenshot of FTX’s book-keeping system showed that even after the massive customer withdrawals, some $10 billion in deposits remained, plus a surplus of $1.5 billion. This led employees to believe wrongly that FTX was on a solid financial footing.

— FTX made about $400 million in “software royalty” payments to Alameda over the years. Alameda used the funds to buy FTX’s digital coin FTT, reducing supply of the coin and supporting its price.

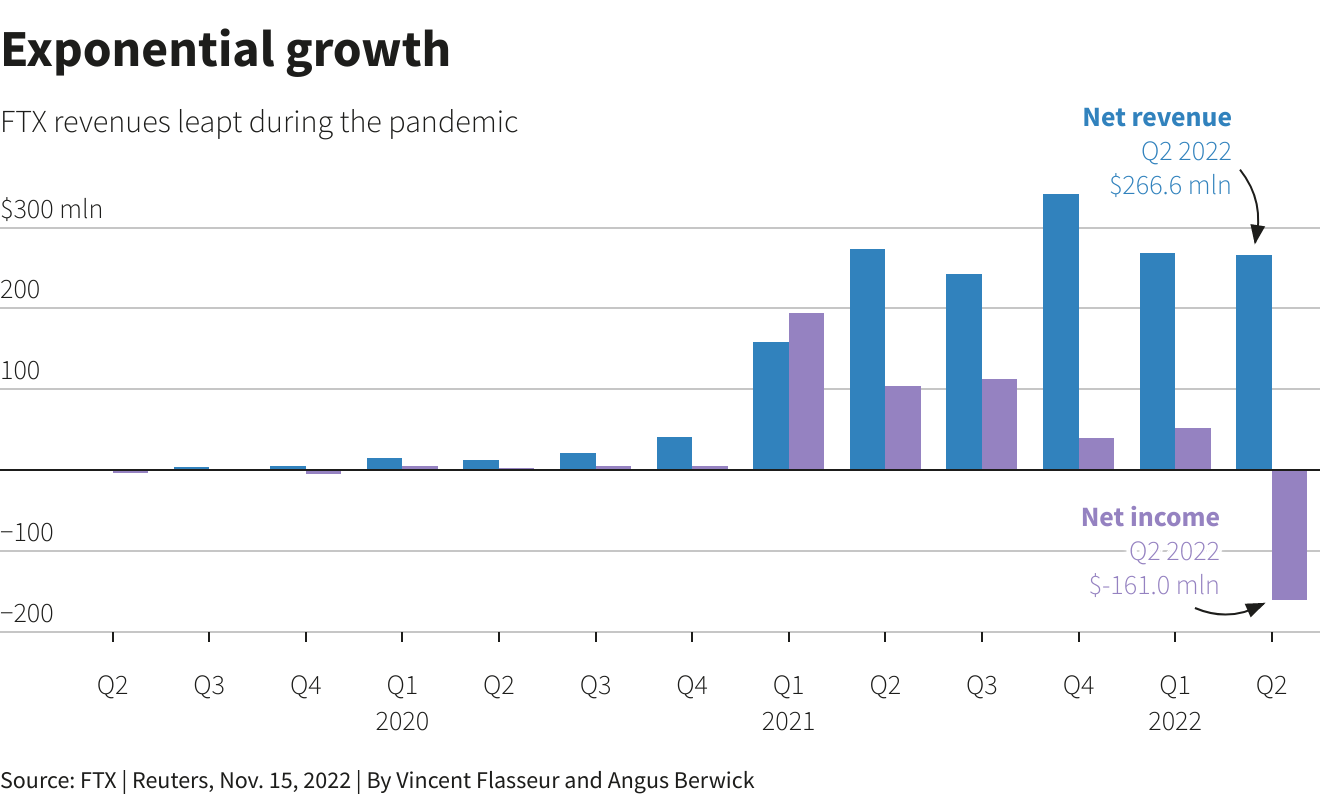

— In the second quarter of this year, FTX posted a $161 million loss. Bankman-Fried, meanwhile, had spent some $2 billion on acquisitions.

— As Bankman-Fried tried to rescue FTX in its frantic final days, he sought emergency investments from financial behemoths in Saudi Arabia and Japan – and was joined at his Bahamas headquarters by his law professor father.

Bankman-Fried told Reuters in an email that due to a “confusing internal account,” Alameda’s leverage was substantially higher than he believed it was. He added that FTX processed roughly $6 billion of client withdrawals.

He said FTX and Alameda together made a profit of roughly $1.5 billion in 2021, which was more than all of the expenses put together of both organizations since their founding. “I was unfortunately unable to communicate much of what was going on to the broader company in real time because much of what I posted in Slack appeared on Twitter soon after,” he added.

FTX did not respond to questions for this article.

The U.S. Department of Justice, Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission are now all investigating FTX, including how it handled customer funds, Reuters has reported. The collapse has shaken investor confidence in cryptocurrencies and led to calls from lawmakers and others for greater regulation of the industry. The CFTC and DOJ declined to comment for this article. The SEC did not respond.

A life in the bahamas

Born in 1992, Bankman-Fried grew up around Stanford University’s Palo Alto-area campus, where both his parents taught at the law school. He landed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he studied math and physics and embraced the idea of effective altruism, a movement that encourages people to prioritize donations to charities.

After graduating from MIT in 2014, he took a job on Wall Street with a quantitative trading firm. Bankman-Fried founded Alameda Research three years later, billing it as “a crypto quant trading firm.”

Rejected initially by venture investors, he cobbled together loans and assembled a team of young traders and programmers, many of them sleeping and working in a small walkup apartment in the San Francisco area, according to a profile that later appeared on the website of FTX investor Sequoia.

Alameda found early trading success by arbitraging cryptocurrency prices on international markets, with half of profits going to charity, according to the same profile. By 2019, the company handled $55 million for clients, an Alameda company booklet said. Reuters could not independently confirm these details.

The booklet flagged the risks of crypto trading, particularly how sudden sales of tokens could trigger a “domino effect” that would lead to a “cascading set of liquidity failures.” It noted that “nothing fundamental” backed bitcoin’s value.

Using profits from Alameda, Bankman-Fried launched FTX in 2019. His aim was to build an “FTX Superapp” that combined cryptocurrency trading, betting markets, stock trading, banking, and peer-to-peer and business payments, according to an FTX marketing document from earlier this year.

The company’s growth over the next two years was only surpassed by his vision.

FTX’s revenues grew from $10 million in 2019 to $1 billion in 2021. From almost nothing in 2019, FTX handled about 10% of global crypto trading this year, a September document shows. It spent roughly $2 billion buying companies, the document shows.

In an undated document, titled ‘FTX Roadmap 2022,’ the company laid out its goals for the next five to 10 years. It hoped to be “the largest global financial exchange,” with $30 billion in annual revenue, more than what U.S. retail brokerage giant Fidelity Investments earned in revenues last year.

In October 2021, Bankman-Fried, then 29 years old, landed on the cover of Forbes, which pegged his net worth at $26.5 billion – the 25th richest person in America. FTX said on its website that “FTX, its affiliates, and its employees have donated over $10m to help save lives, prevent suffering, and ensure a brighter future.”

Bankman-Fried’s personal finances suggest he lived frugally for a billionaire. A financial statement reviewed by Reuters shows that for 2021, he drew an annual salary of $200,000, declared $1 million in real estate assets, and spent $50,000 on personal expenses.

But in the Bahamas, his lifestyle was more luxurious than his finances showed. At one point, he lived in a penthouse overlooking the Caribbean, valued at almost $40 million, according to two people who worked with FTX.

Bankman-Fried told Reuters he lived in a house with nine other colleagues. For his employees, he said FTX provided free meals and an “in-house Uber-like” service around the island.

“ULTIMATE SOURCE OF TRUTH”

This year began with FTX seemingly everywhere.

Its logo was emblazoned on a major sports arena in Miami and on Major League Baseball umpire uniforms. Sports stars and celebrities including Tom Brady, Gisele Bundchen and Steph Curry became partners in promoting the company. None of them commented for this article. Bankman-Fried became a regular presence in Washington, donating tens of millions of dollars to politicians and lobbying lawmakers on crypto markets.

FTX was also planning partnerships with some of the world’s largest companies. An FTX document from June 2022, which has not been previously reported, shows a list of FTX’s “select partners” for business-to-business (B2B) services. Prospective partners included retail giant Walmart Inc, social media titan Meta Platforms Inc, payment-system provider Stripe, and financial website Yahoo! Finance, according to the document.

A Yahoo spokesperson said, “While we were in very early stages of a prospective partnership with FTX, nothing was close to completion when the events of last week occurred.”

A person with knowledge of the matter said Stripe has no contract with FTX to enable Stripe users to accept crypto payments. Walmart didn’t respond to a request for comment about a proposed partnership with FTX for employee investing. Meta too didn’t comment about discussions to make FTX a digital-wallet provider for Instagram users.

Investors loved Bankman-Fried’s ambition. FTX had already received more than $2 billion from backers including Sequoia, SoftBank Group Corp, BlackRock Inc and Temasek. In January, FTX raised a further $400 million, valuing the business at $32 billion.

FTX expected to take its international and U.S. businesses public, an investor due-diligence document from this June said. The document is reported here for the first time.

At the peak of his powers, Bankman-Fried urged the crypto industry to help governments shape laws to supervise it, saying FTX’s goal was to become “one of the most regulated exchanges in the world.” “FTX has the cleanest brand in crypto,” it proclaimed earlier this year.

Behind his rapid growth, there was a secret Bankman-Fried kept from most other employees: he had dipped into customer funds to pay for some of his projects, according to company documents and people briefed on FTX’s finances. Doing so was explicitly barred in the exchange’s terms of use, which affirmed user deposits “shall at all times remain with you.”

FTX generated 2 cents in fees for every $100 traded, documents seen by Reuters show, reaping hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue by 2021. Nonetheless, FTX barely broke even during its first two years, 2019 and 2020. It generated around $450 million in profit in 2021, when crypto markets boomed, but it slumped to a $161 million loss in the second quarter of this year, according to financial records, which are reported here for the first time.

Some of the $10 billion in removed customers’ money went to cover losses that Alameda sustained earlier this year on a series of bailouts, including in failed crypto lender Voyager Digital, according to the three FTX sources briefed on the company’s finances.

FTX also financed acquisitions such as the purchase in May of a $640 million stake in trading platform Robinhood Markets Inc. Robinhood didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Bankman-Fried told Reuters he did not believe that Alameda had substantial losses, including on Voyager, without providing further details.

Around $1 billion of the $10 billion sum is not accounted for among Alameda’s assets, Reuters reported on Friday. Reuters has not been able to trace these missing funds.

According to the three FTX sources, only Bankman-Fried’s innermost circle of associates knew about his use of client deposits: his co-founder and chief technology officer, Gary Wang; the head of engineering, Nishad Singh; and Caroline Ellison, chief executive of Alameda. Wang and Singh both worked with Bankman-Fried at Alameda previously.

Wang, Singh and Ellison did not return requests for comment.

To conceal the transfers of customer funds to Alameda, Wang, a former Google software developer, built a backdoor in FTX’s book-keeping software, the people said.

Bankman-Fried often told employees tasked with monitoring the company’s financials that the book-keeping system was “the ultimate source of truth” about the company’s accounts, two of the people said. But the backdoor, known only to his most trusted lieutenants, allowed Alameda to withdraw crypto deposits without triggering internal red flags, they said.

FTX also had a vulnerability: its bespoke cryptocurrency.

Shortly after its launch, FTX introduced its own digital token, called FTT, described on its website as the exchange’s “backbone.” Staff could opt to receive pay and bonuses in the token, and many of them accumulated fortunes in FTT as its value exploded in 2021, according to the three current and former executives. One executive invested all their savings in FTT, worth millions of dollars, the executive said, “because of loyalty to Sam.”

According to a June 2022 due diligence document Bankman-Fried sent to a potential investor and the company’s financial records, FTX paid $400 million to an Alameda subsidiary since 2019 as “software royalty” payments for development work. The subsidiary used the funds to buy FTT and remove the digital tokens from supply, so supporting the price.

FTX disclosed on its website that it was using part of its trading fees to buy FTT. It did not reveal the arrangement with Alameda.

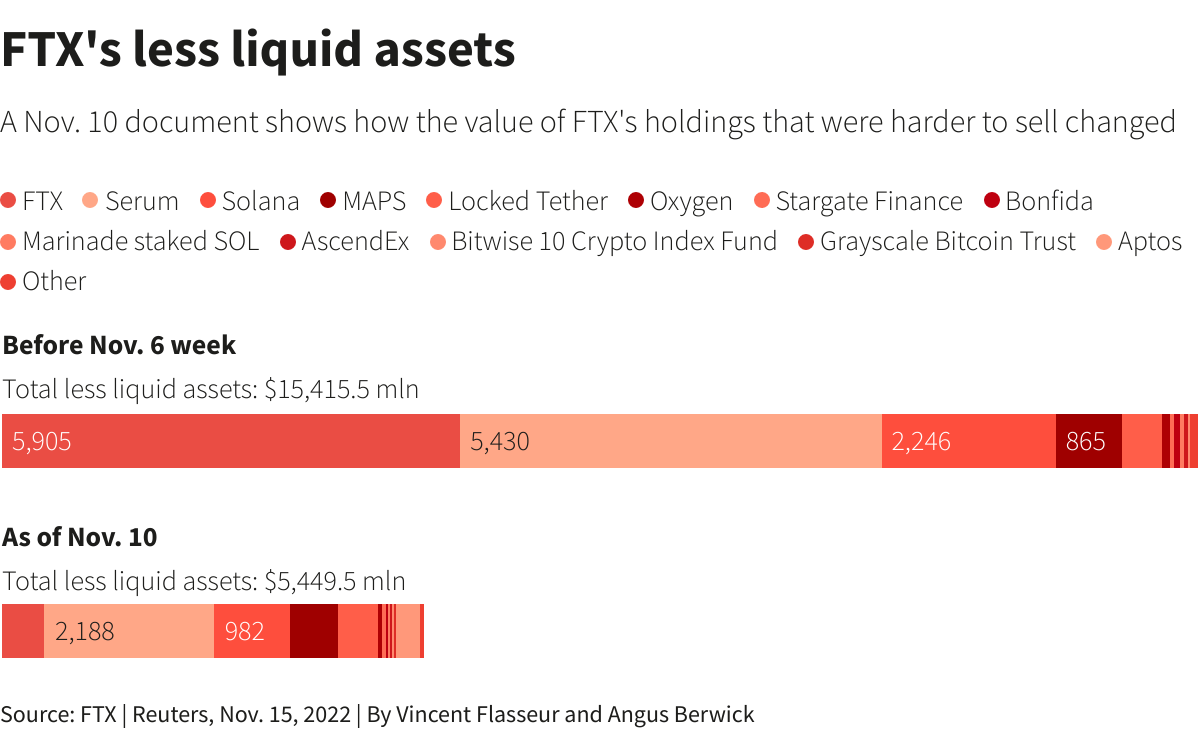

Over the years, Alameda accumulated a huge holding of FTT, valued at around $6 billion before last week, according to a balance sheet later sent to investors. It used the FTT reserves to secure corporate loans, people familiar with its finances said. This meant that Bankman-Fried’s business empire was dependent on the token.

That little-known holding became Bankman-Fried’s undoing.

Pressure builds

On Nov. 2, news outlet CoinDesk reported a leaked balance sheet disclosing Alameda’s reliance on FTT. The head of the world’s largest crypto exchange – Bankman-Fried’s chief rival – pounced on that report. Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao, citing “recent revelations,” said Binance would sell its entire FTT holding due to “risk management.”

Bankman-Fried retorted on Twitter that Zhao was spreading “false rumors.” In a since-deleted tweet, he wrote: “FTX has enough to cover all client holdings. We don’t invest client assets.”

Nonetheless, FTT came under intense selling pressure, forcing Alameda to buy more of the tokens in an attempt to stabilize the price, a person with knowledge of the trades said. Customers panicked and rushed to withdraw deposits from FTX, with over $100 million flowing out of the firm each hour that Sunday, company documents reviewed by Reuters show.

In his email to Reuters, Bankman-Fried said, “To my knowledge, Alameda did not buy very much FTT during the crash to stabilize it.”

Staff initially remained calm. The finance team could still see ample assets on the book-keeping portal as of last week. About $10 billion in client deposits remained, with a $1.5 billion surplus to cover any further withdrawals, according to a screenshot of the database seen by Reuters.

In reality, those funds were gone.

Several hours after Zhao’s Sunday tweet, Bankman-Fried has told Reuters, he gathered his lieutenants Wang and Singh at his apartment to decide on a plan. It was a “rough weekend,” he messaged staff on Slack that evening, but “we’re chugging along.”

The following day, he summoned several other senior managers to his home to join Wang and Singh. He broke the news to them: FTX was almost out of money.

This account of the scramble that ensued is based on interviews with three current and former FTX executives briefed by top staff and documents that Reuters reviewed.

Bankman-Fried showed the executives spreadsheets that revealed there was a $10 billion hole in FTX’s finances – because customer deposits had been transferred to Alameda and mostly spent on other assets. The executives were shocked. One of them told Bankman-Fried the spreadsheet presentation contradicted what FTX told regulators about its use of client funds.

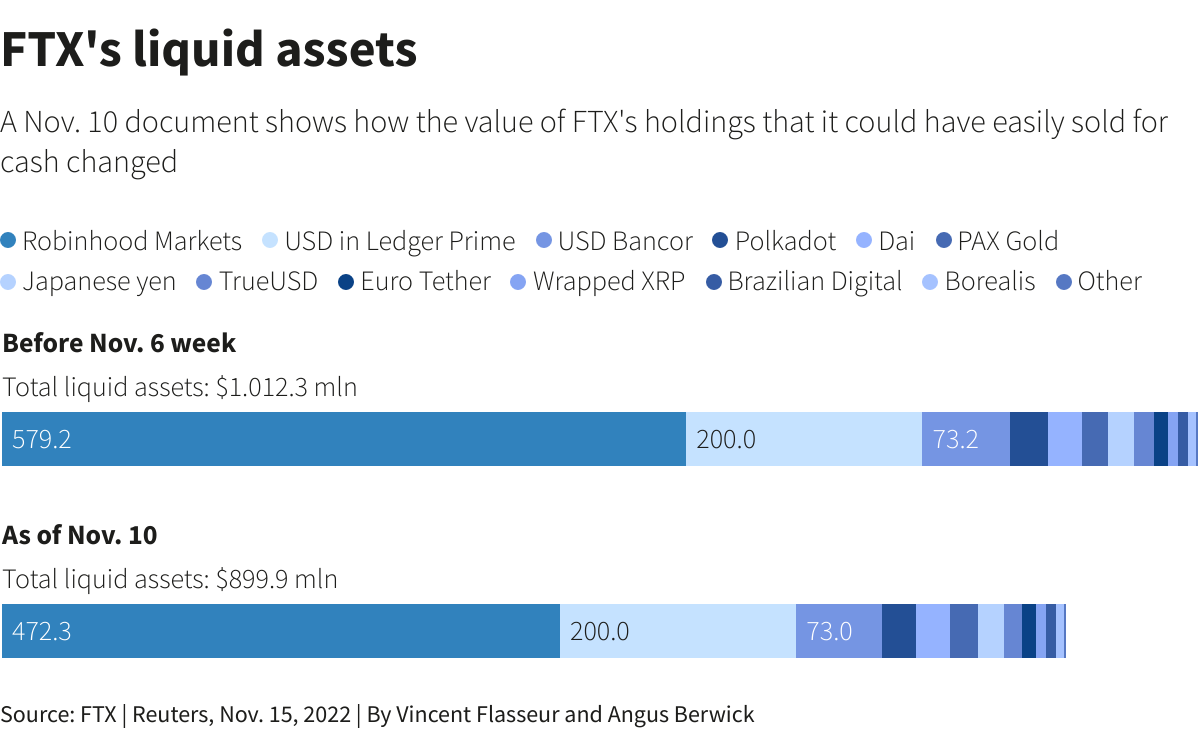

To make up the shortfall, they calculated that Alameda could sell around $3 billion of the assets within hours, mainly money held in company trading accounts on other crypto exchanges. The rest would take days or weeks to offload because it was hard to trade those assets. And FTX urgently needed a further $7 billion in cash to survive.

So began Bankman-Fried’s search for a savior.

While money continued to drain away from FTX, the three sources told Reuters, he and his aides worked through the night, contacting about a dozen potential investors.

He turned to the crypto community, too, ringing up the organization behind Tether, the world’s largest stablecoin, and asking for a loan. His father, Joseph Bankman, a Stanford Law professor, also arrived to advise his son. Bankman did not respond to a request for comment. In return for any funding, Bankman-Fried pledged to investors most of Alameda’s assets, including its holding of FTT, along with his own 75% stake in FTX. But no one came through with an offer.

One of the investors who turned down Bankman-Fried said his numbers were “very amateurish,” without elaborating. Another red flag was that the spreadsheets showed ties between FTX and Alameda, the investor said.

Around 3 a.m., Bankman-Fried resorted to Zhao, his archrival at Binance. Zhao, widely known by the initials CZ, came to the phone. A few hours later, Zhao sent over a non-binding letter of intent to acquire FTX.com, which Bankman-Fried signed. The pair tweeted a joint announcement later that morning.

For most FTX employees, this was the first they heard about the company’s dire situation. “Just complete disbelief and feelings of betrayal,” Zane Tackett, FTX’s head of institutional sales, wrote on Twitter the day after. He declined to comment.

Tackett and some others resigned. “I can’t do it any more,” another FTX team member texted colleagues.

To worsen the pain, the price of the FTT token crashed 80% within three hours of the news, shrinking Alameda’s assets further and wiping out many employees’ net worth. The executive with millions of dollars in FTT said watching it collapse “was like seeing my world diminishing.”

Bankman-Fried pleaded for employees’ forgiveness on Slack, saying he “fucked up” but that the Binance deal allowed them to “fight another day.” Less than 30 hours later, Binance pulled out, citing its due diligence. Sequoia then wrote off its $150 million investment in FTX.

Scrambling to find a savior, Bankman-Fried expanded his search around the world. “I’ll keep fighting,” he messaged staff.

He sought to persuade officials at major financial institutions such as Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund and Japanese investment bank Nomura Holdings Inc to invest, according to a message he sent on Thursday to advisors, along with two other people familiar with the talks. Those appeals are reported here for the first time. PIF and Nomura did not comment.

Bankman-Fried also tried to get a group of crypto firms to each pitch in $1 billion. But a balance sheet FTX sent to investors, showing only $900 million in liquid assets, spooked them, according to two people familiar with the matter.

By Friday, when FTX filed for bankruptcy in the United States, “we were all doomed,” an executive said.

(Reporting by Angus Berwick and Anirban Sen in NEW YORK, Elizabeth Howcroft in LONDON and Lawrence Delevingne in BOSTON; additional reporting by Tom Wilson in LONDON, Greg Roumeliotis in NEW YORK and Hannah Lang in WASHINGTON; editing by Paritosh Bansal and Janet McBride)

About the Author

Reuterscontributor

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest international multimedia news provider reaching more than one billion people every day. Reuters provides trusted business, financial, national, and international news to professionals via Thomson Reuters desktops, the world's media organizations, and directly to consumers at Reuters.com and via Reuters TV. Learn more about Thomson Reuters products:

Latest news and analysis

Advertisement