Advertisement

Advertisement

UK Credit Impulse Contracts for Seven Consecutive Quarters

Published: Jun 23, 2019, 15:37 GMT+00:00

There has been a handful of good data released in the United Kingdom in recent weeks but it would be misleading to see this as a sign that growth is on the verge of a prolonged rebound.

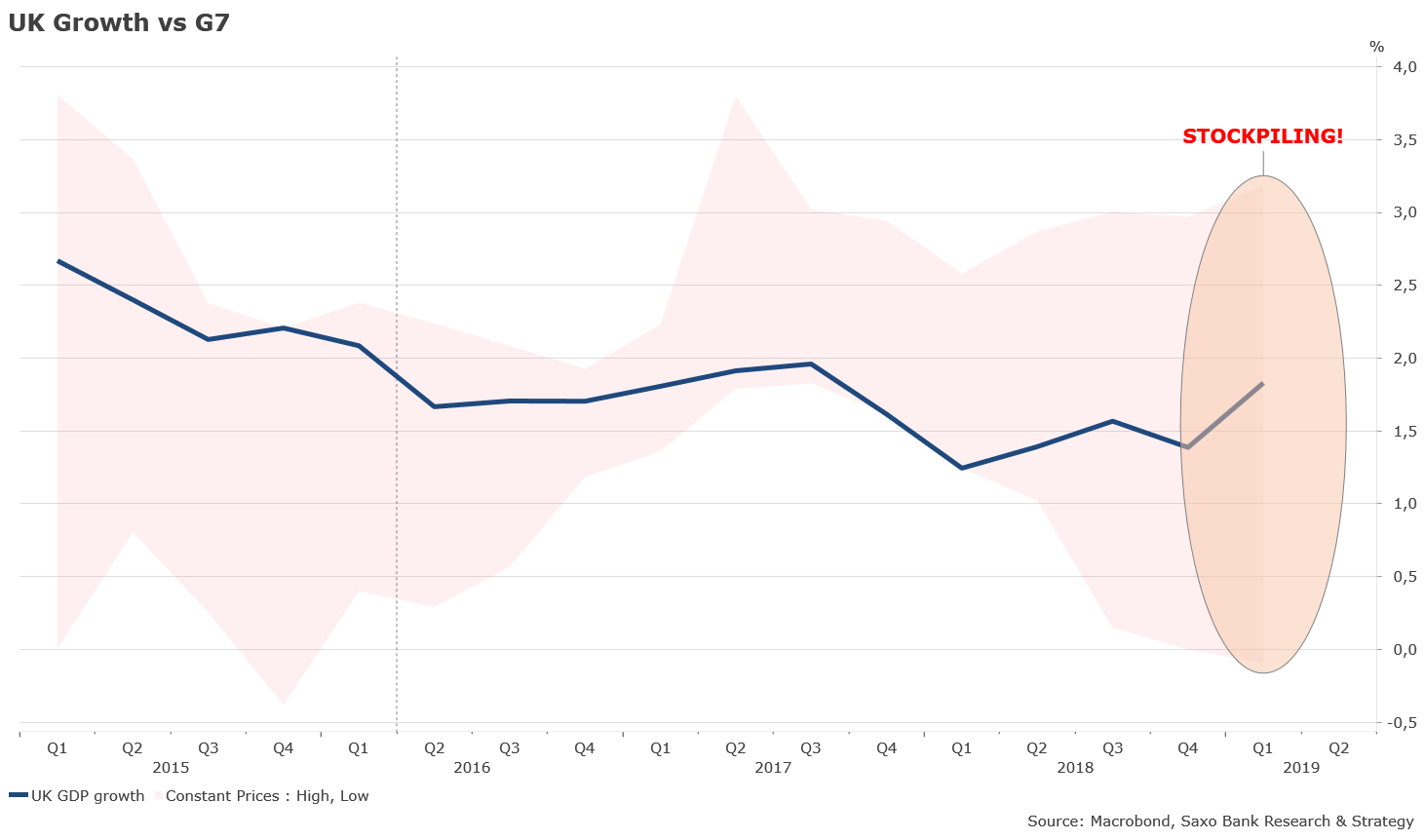

In fact, the UK economy is going through a false stabilisation that won’t last long. Q1 UK growth has returned to the average of the G7 countries, but this is mostly due to stockpiling ahead of March 31, the initial Brexit deadline. This is not the sign of a very dynamic economy in our view. It also primarily reflects lower growth momentum in the G7, not real stronger momentum in the UK. In addition, consumer surveys are rebounding but this is mostly caused by higher wages (+3.4% YoY in Q1 2019 according to the latest OECD update) and postponed Brexit.

We identify a bunch of risks that could derail growth in coming quarters:

- The likelihood of no-deal Brexit at the end of October 2019.

- Deterioration in the trade war front that could impact more negatively the global supply chain.

- The lack of money supply growth in main economies is leading to low growth until at least mid-end of 2020.

- The risk of recession in the US has significantly increased for 2020. Based on leading indicators, the probability is now comparable to the probability measure in advance of the last 3 recessions.

- Rising tensions between the United States and Iran in the oil-strategic routes of the Strait of Hormuz that could lead to disruptions in the global oil market.

More fundamentally, even if none of these events materialises, which is rather unlikely, the UK economy is condemned to a prolonged period of low growth. The number one issue of the British economy is not really Brexit but the lack of new credit growth which is essential in a highly leveraged economy.

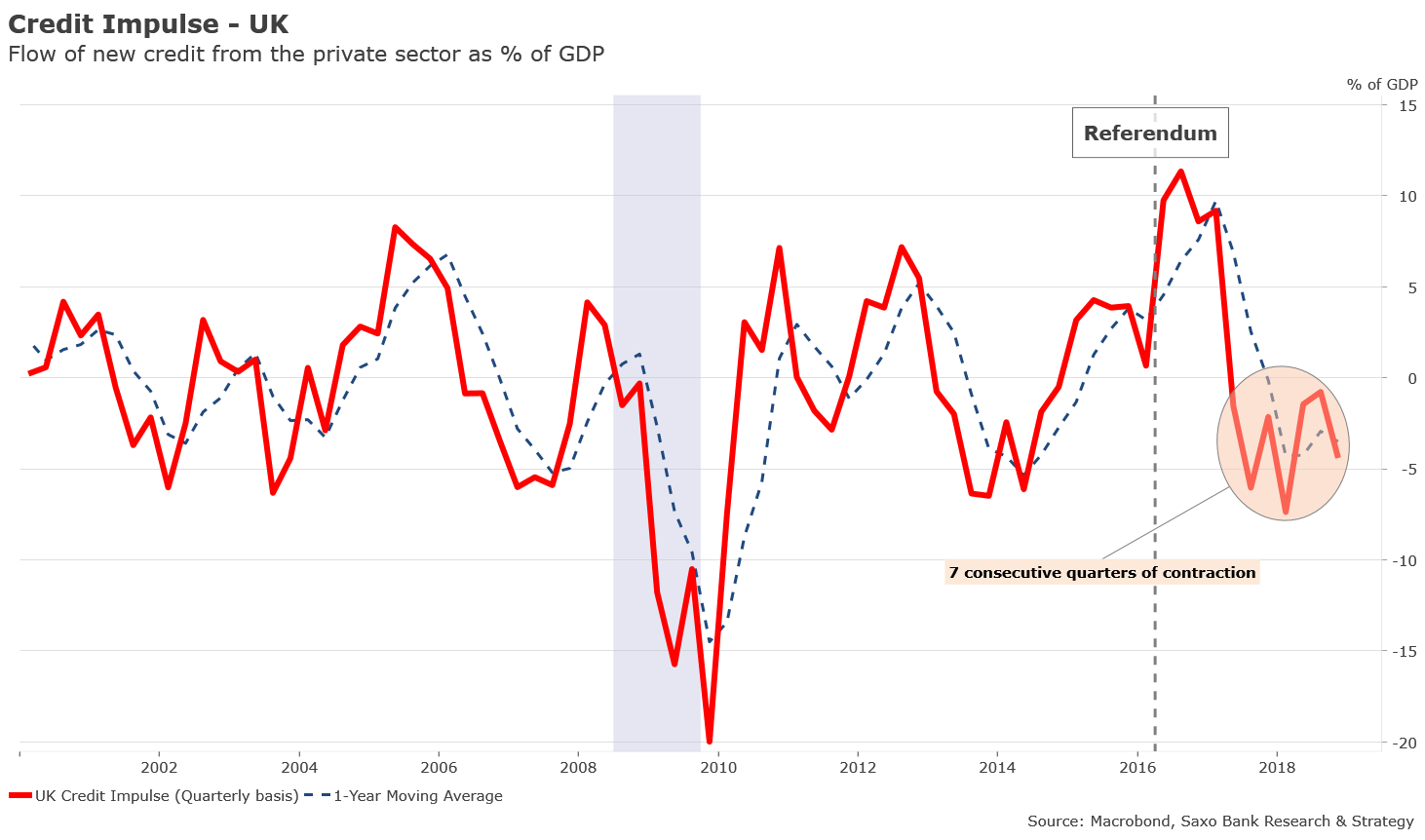

Our leading indicator, the credit impulse, is tracking the flow of new credit in the economy and explains economic activity nine to twelve months forward with an “R2” of .60. As of now, UK credit impulse has been in contraction for seven consecutive quarters and is currently running at minus 4.4% of GDP. The length of the contraction is similar to that of the GFC but with a smaller amplitude. The lowest point reached in the post-referendum area was minus 7.4% of GDP versus a drop up to minus 20% of GDP in 2009.

Prolonged contraction in UK credit impulse marks the end of the massive credit boom that started in 2015 and lasted until 2017 and will ultimately constraint in the long run private consumption, which contributes to roughly 60% of GDP.

In the chart below, we have plotted the evolution of the flow of new personal loans and overdrafts since 2002 as a proxy of UK household financial stress. It has been in contraction since April 2018 and is currently back to where it was in 2011, at minus 1.8% of GDP.

Real higher wages are bringing some relief to UK consumers at the moment, pushing a bit up the saving rate from historically low level of 3% reached after the referendum, but it is likely to be short-lived as Brexit – no matter which trade and political agreements will prevail with the EU – will undoubtedly have negative ripple effects on businesses, labor market and growth due to higher uncertainty. In a more constrained economic environment, companies will be more reluctant than now to keep lifting pay by cutting their margins, even in a context of full employment.

On the top of that, the risk of policy error has significantly increased. In 2010, the credit cycle has rebounded very fast and strongly after recession due to the Bank of England lowering interest rates and the massive injections of liquidity in the financial system. In post-Brexit UK, such a stimulus is unlikely. The BoE has lately sent very mixed messages about the next move of monetary policy, pointing out risks to growth at its latest Monetary Policy Committee meeting but also expressing concerns about household inflation expectations that keep increasing above 3% up to 5 years.

Though it is getting more or more likely that the next move will be an interest cut rather than a hike, the UK central bank has less room than the Fed and the European Central Bank to stimulate growth in a context of high inflation expectations. This monetary policy dilemma makes a move in terms of fiscal policy even more urgent than before to mitigate the Brexit impact.

Christopher Dembik, Head of Macro Analysis at Saxo Bank.

This article is provided by Saxo Capital Markets (Australia) Pty. Ltd, part of Saxo Bank Group through RSS feeds on FX Empire.

About the Author

Christopher Dembikcontributor

Christopher Dembik joined Saxo Bank in 2014 and has been the Head of Macro Analysis since 2016.

Advertisement