Advertisement

Advertisement

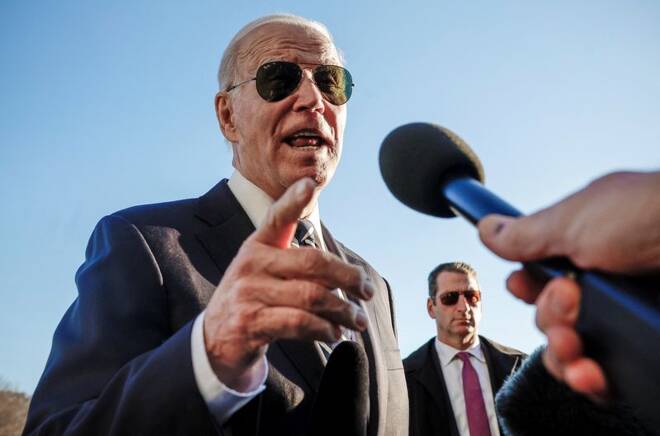

Biden White House, McCarthy dig in ahead of debt meeting

By:

By Trevor Hunnicutt and David Morgan WASHINGTON (Reuters) - U.S. President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy won't come to their first meeting over raising the debt ceiling with any specific proposals to stave off a possible default, both sides indicated on Tuesday.

By Trevor Hunnicutt and David Morgan

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. President Joe Biden and House of Representatives Speaker Kevin McCarthy won’t come to their first meeting over raising the debt ceiling with any specific proposals to stave off a possible default, both sides indicated on Tuesday.

Instead, the Wednesday meeting between Biden and McCarthy is likely to serve as the opening bell for months of back-and-forth maneuvering over raising the United States’ $31.4 trillion borrowing cap.

Neither side is showing signs they’re willing to negotiate on anything just yet. Failure to reach agreement could lead to a possible default on U.S. debt as early as June.

Republicans in the House have said any debt-ceiling hike should be paired with steep spending cuts. The White House says it will only discuss future spending cuts after the debt ceiling is raised.

Biden will call on McCarthy to release a budget plan in the meeting and to commit to support the nation’s debt obligations, according to a White House memo seen by Reuters.

“Raising the debt ceiling is not a negotiation; it is an obligation of this country and its leaders to avoid economic chaos,” White House economic adviser Brian Deese and director of the Office of Management and Budget Shalanda Young wrote.

McCarthy, for his part, said Biden needs to be willing to make concessions in order to get a debt-ceiling hike though Congress.

“The first thing they should do, especially as the President of the United States, (is) say he’s willing to sit down and find a common ground and negotiate together,” McCarthy told reporters in the U.S. Capitol.

Unlike most other developed countries, the United States puts a hard limit on how much it can borrow, and Congress must periodically raise that cap because the U.S. government spends more than it takes in.

The debt ceiling increase is usually voted in on a bipartisan basis, but Republicans have used their leverage previously to win spending cuts.

Biden seemed to question McCarthy’s ability to keep Republicans in line Tuesday at a fundraiser in New York, calling McCarthy “a decent man, I think,” but noting the concessions he had to make to conservatives to become speaker.

“Look what he had to do, and to make commitments that are just absolutely off the wall for a Speaker of the House to make in terms of being able to become a leader.”

Detailed proposals may not emerge for several weeks.

The White House has said it would release its budget proposal on March 9. House Republicans, meanwhile, will aim to produce their budget proposal in April, said House Republican Leader Steve Scalise.

“I hope the president meets his deadline just like we’re going to work to meet our deadline,” Scalise said at a news conference.

The White House has seized on the lack of consensus to highlight fringe proposals from some Republicans, including one that abolishes the Internal Revenue Service in favor of a higher sales tax and one that trims Social Security retirement benefits.

McCarthy has ruled out cuts to Social Security and Medicare, the two largest government benefit programs.

“You got to remember, you got a president here who’s never been in business… And he’s saying, ‘I’m not going to talk to you about the debt ceiling?,'” said Roger Williams, a House Republican, while exiting a conference meeting.

“It’s ridiculous. So maybe we can get that out of the way tomorrow with their meeting, and we begin to talk about what we can add and what we can subtract.”

Past showdown

A 2011 debt ceiling showdown between Democratic President Barack Obama and House Republicans took the country to the brink of default and prompted a first-ever downgrade of the country’s top-notch credit rating.

Veterans of that battle warn that the politics and math are tougher this time around, making it more difficult to find a resolution until the government is about to run out of money – or after it has.

“I think that the possibility of miscalculation runs higher today than it did in 2011,” said Neil Bradley, a former House Republican leadership aide who is now a top official at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

The showdown over the growing U.S. debt threatens to roil the global economy if the United States defaults.

The Treasury Department has already started taking “extraordinary measures” to stave off a default until summer after hitting the U.S. government’s $31.4 trillion borrowing limit earlier in January.

(This story has been corrected to change “billion” to “trillion” in paragraph 2. The error first occurred in the previous version of this story.)

(Additional reporting by Nandita Bose; writing by Andy Sullivan; Editing by Heather Timmons, Jonathan Oatis and Alistair Bell)

About the Author

Reuterscontributor

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest international multimedia news provider reaching more than one billion people every day. Reuters provides trusted business, financial, national, and international news to professionals via Thomson Reuters desktops, the world's media organizations, and directly to consumers at Reuters.com and via Reuters TV. Learn more about Thomson Reuters products:

Latest news and analysis

Advertisement