Advertisement

Advertisement

Column-U.S. corporate profit boom reveals more about inflation threat than wages: McGeever

By:

By Jamie McGeever ORLANDO, Fla. (Reuters) - While the Federal Reserve and other central banks obsess over avoiding a 1970s style 'wage-price' spiral, U.S. GDP data last week showed that the risk of inflation remaining elevated is more nuanced.

By Jamie McGeever

ORLANDO, Fla. (Reuters) – While the Federal Reserve and other central banks obsess over avoiding a 1970s style ‘wage-price’ spiral, U.S. GDP data last week showed that the risk of inflation remaining elevated is more nuanced.

Call it a ‘profit-price’ spiral.

By many measures, the U.S. labor market is as strong as it has been for decades. As labor is the biggest single input into firms’ total costs, policymakers are right to fret that ‘excessive’ wage demands may stoke or even accelerate inflation.

But looked at through the prism of profits, corporate America is also in rude health, especially big business. In the second quarter this year U.S. companies raked in profits that, depending on the cut, were the highest on record, or close to levels not seen in over half a century.

This is an inflationary threat too, but we hear far less from policymakers about it than the risk of wages fueling a price spiral that would only be crushed by interest rate increases like those administered by former Fed Chair Paul Volcker in the early 1980s.

The battle between labor and capital, which saw capital take an ever-growing share of national income over the past 30 years, is not a new issue, certainly not politically.

But with inflation at a four-decade high, it is emerging as a policymaking challenge, one the Fed has to take on board, says Chris Zaccarelli, chief investment officer at Independent Advisor Alliance.

“I’m sure higher corporate profits are, indirectly, encouraging the Fed to increase interest rates. To the extent that prices are rising everywhere and corporate profits are staying high, those are a direct corollary to higher inflation,” he said.

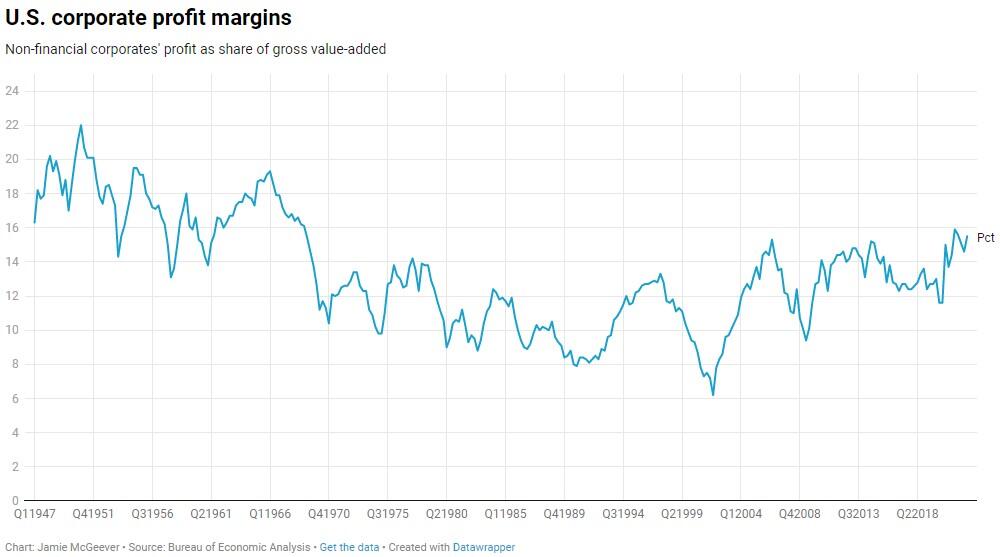

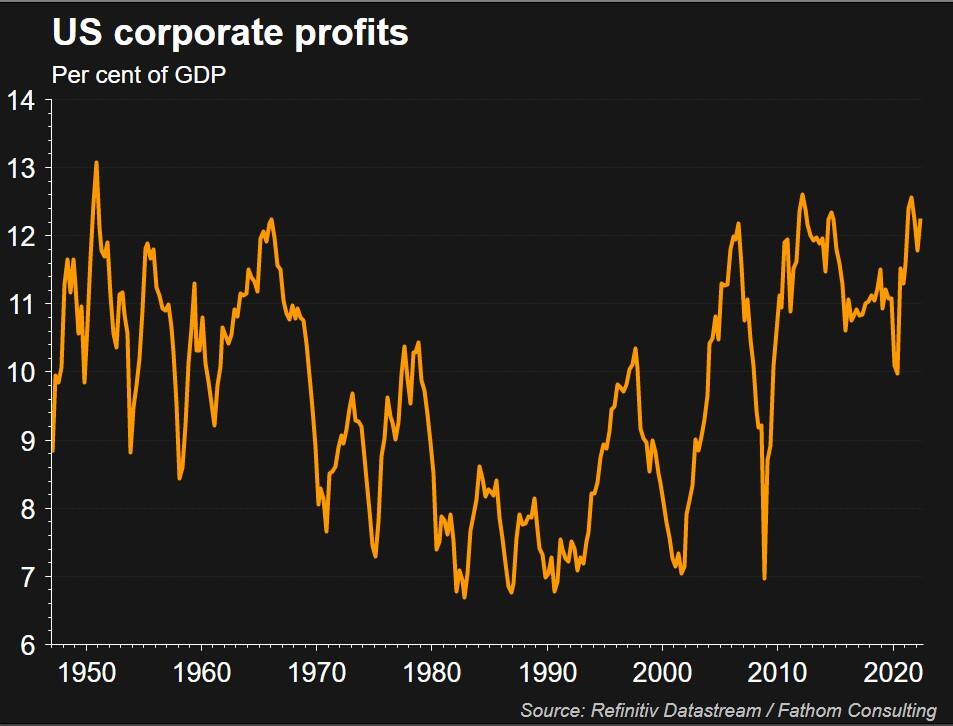

As a share of GDP, U.S. corporate profits in the second quarter rose to 12.25%, around their highest levels since 1950. Profit margins for non-financial firms rose to 15.5% in the same period, closing in on last year’s peak going all the way back to the 1960s.

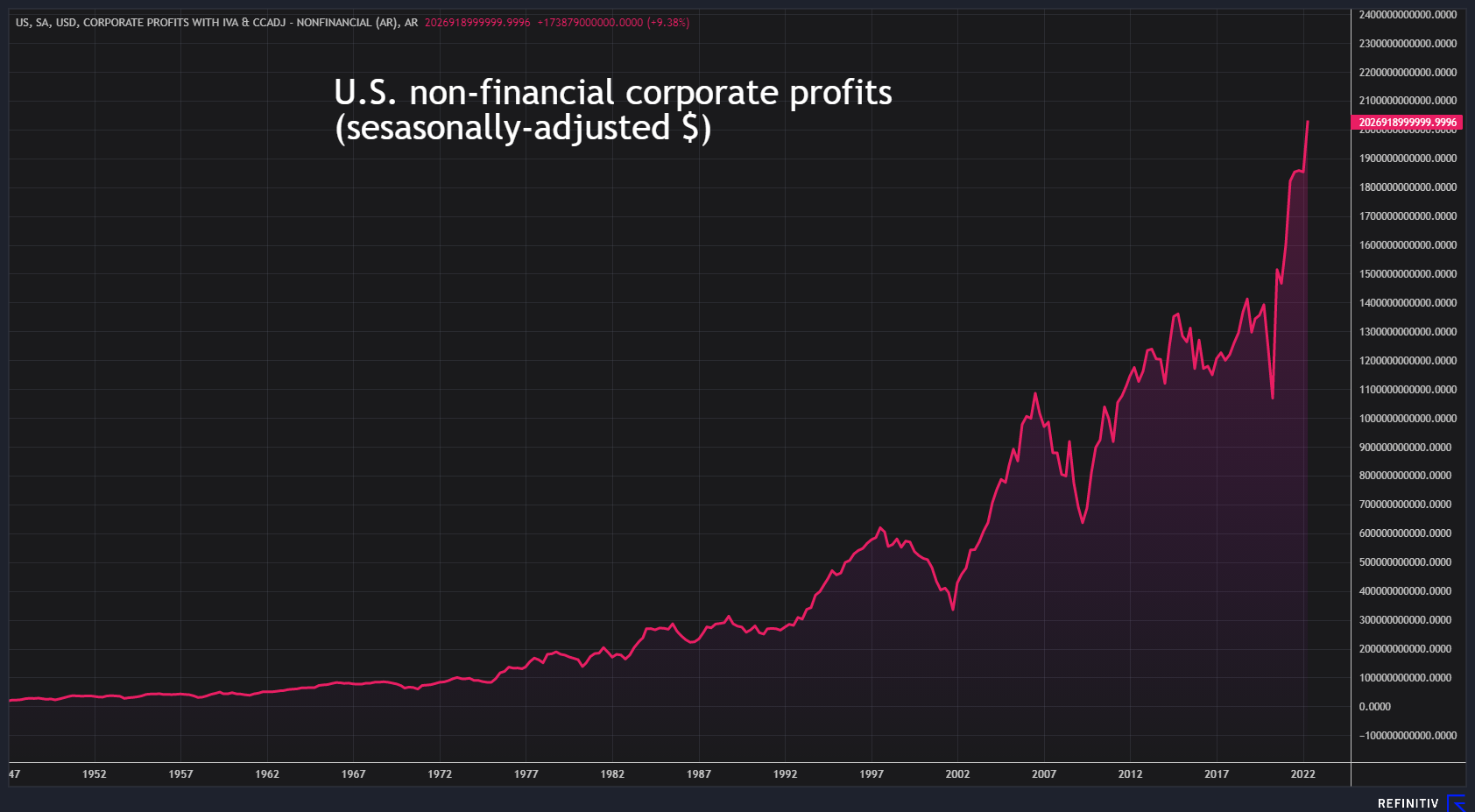

Less surprisingly, perhaps, nominal profits in Q2 were the highest ever. Still, the burst through the $2 trillion barrier is noteworthy.

This comes at the same time U.S. labor market conditions are the tightest in decades also. The unemployment rate was last lower than today’s 3.5% over half a century ago, and there are two job openings for every unemployed person.

While worker strikes and labor disputes are less likely in the United States than in Europe, Fed officials would not welcome wage growth matching inflation, far less exceeding it.

They would argue this would have one of two consequences, both of which go against their dual mandate of price stability: higher wages are passed onto consumers, leading to even higher inflation; or firms simply cut back on staff.

Unfair burden?

Fiscal policy is more suited to curbing U.S. corporate pricing power. As Robert Reich, professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a former Labor secretary, notes, the Biden administration passed a 1% tax on stock buybacks in the recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act, and a minimum corporate tax.

This doesn’t go far enough, he argues, but recognizes that policies such as a windfall profits tax, price controls, higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy, and bolder antitrust enforcement face stiff opposition in Washington.

Absent a powerful fiscal push, the onus falls on the Fed to use the blunt instrument of job-sapping and recession-seeding higher interest rates.

“This is the only tool in the Fed’s tool kit. The problem is that this puts most of the burden of fighting inflation on average working people and the poor,” Reich told Reuters.

GRAPHIC: U.S. real earnings growth (https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/egpbkrndqvq/USRealEarnings.jpg)

There’s little doubt that Fed communications focus on the risks posed by wage pressures more than corporate pricing.

Minutes of the Fed’s July 26-27 policy meeting reveal seven mentions of ‘wage’ or ‘wages’, 17 of ‘labor market’, eight of ‘job’ or ‘jobs’, and not one of ‘profit’.

Transcripts of Fed chief Jerome Powell’s press conference on July 27 show nine references to ‘wage’ or ‘wages’, 38 mentions of ‘labor market’, 15 mentions of ‘job’ or ‘jobs’, but not a single mention of ‘profit’, ‘corporate’, ‘company’, or ‘companies’.

If the political establishment in Washington is unwilling and, the Fed is unable, to cool the corporate profit boom’s potential price pressures, maybe the economy will do it for them.

As tighter financial conditions slow activity and demand, profit growth should cool and companies’ margins should decline.

“Earnings growth is slowing down and heading towards zero. This implies pressure on the margin, which the consensus now forecasts to decline by 5% in 2022,” equity analysts at Societe Generale wrote on Thursday.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.)

(By Jamie McGeever; Editing by Andrea Ricci)

About the Author

Reuterscontributor

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest international multimedia news provider reaching more than one billion people every day. Reuters provides trusted business, financial, national, and international news to professionals via Thomson Reuters desktops, the world's media organizations, and directly to consumers at Reuters.com and via Reuters TV. Learn more about Thomson Reuters products:

Latest news and analysis

Advertisement