Advertisement

Advertisement

Stumbling Treasury rally clouds bond market outlook for 2023

By:

By Davide Barbuscia NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. government bond investors hurting after the biggest annual decline in the history of the asset class are riding out yet another selloff, as worries over persistent inflation cloud the prospects for an expected 2023 rebound.

By Davide Barbuscia

NEW YORK (Reuters) – U.S. government bond investors hurting after the biggest annual decline in the history of the asset class are riding out yet another selloff, as worries over persistent inflation cloud the prospects for an expected 2023 rebound.

Heavyweights such as Amundi, Vanguard and BlackRock turned bullish on bonds in recent weeks, on expectations that inflation has peaked and that a potential recession next year could push the Federal Reserve to end its most aggressive rate hiking cycle in decades. Many investors have followed suit. December’s BofA Global Research survey showed fund managers were the most overweight bonds versus stocks in nearly 14 years.

But while bonds rebounded in October and November, prices have retreated over the last few weeks, as investors digested stronger-than-expected U.S. economic data and as China reopened from COVID-19 restrictions, which some believe could add to price pressures in the new year.

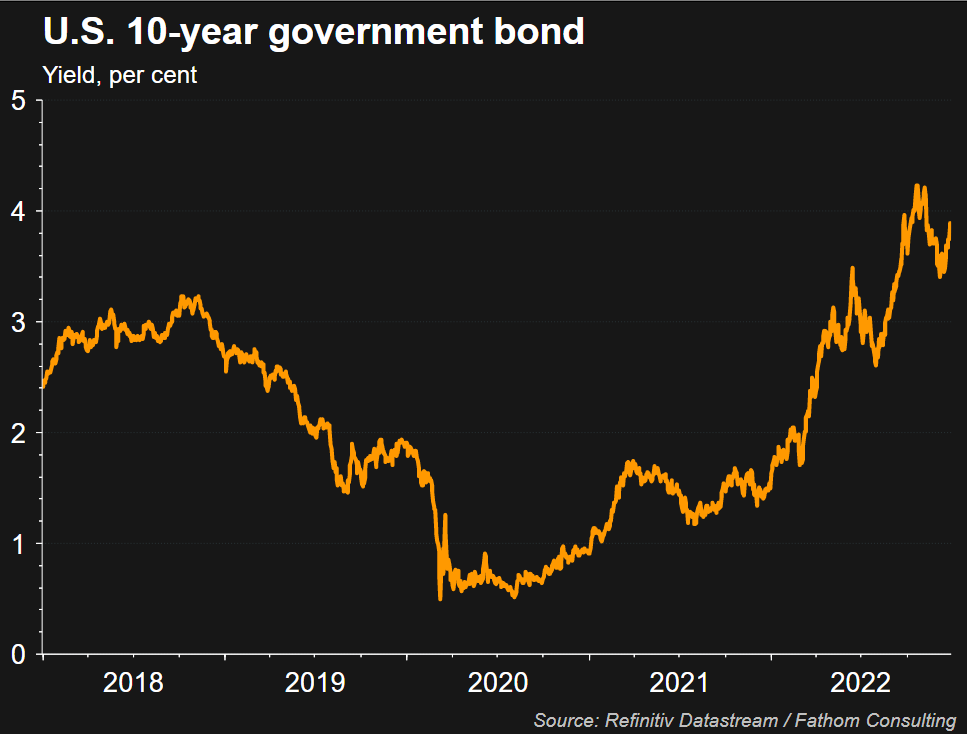

Falling prices have pushed up yields, which move inversely. Benchmark 10-year Treasury yields have climbed over 40 basis points since mid-December to nearly 3.9%, the highest in over a month. Two-year yields – which more closely reflect monetary policy expectations – hit an intra-day peak of 4.445% on Tuesday, their highest since November.

“The market seemed to have been getting ahead of itself expecting a pivot to occur from the Fed,” said Michael Reynolds, vice president of investment strategy at Glenmede. “It is coming to terms with the fact that the Fed is going to have to be tighter for longer, until they’re really sure that they’ve got inflation back under control.”

Wall Street’s record for end-of-year bond market predictions has taken a hit. Late-2021 forecasts from Barclays, Goldman Sachs and other big banks largely failed to predict the carnage markets would endure this year, which saw the ICE BofA US Treasury Index slide 13% for its biggest annual loss in history as the Fed rapidly raised interest rates to thwart surging inflation.

Among banks forecasting a decline in the benchmark 10-year yield next year are Deutsche Bank which sees the yield at year-end at 3.65% and Bank of America which expects a year-end 3.25% yield. Investors in futures markets believe the Fed will begin cutting rates in the second half, though the central bank has projected interest rates steadily rising into the end of 2023 to stand around 70 basis points above current levels.

Several global and domestic developments are complicating the case for lower yields. China’s rollback of stringent COVID-19 policies may support global growth and mitigate a widely expected recession. It also threatens to push inflation higher.

While the pace of U.S. inflation subsided in October and November, comparatively robust employment and other signs of strength in the economy have implied the Fed may have room for further monetary tightening.

“If the economy does not weaken further overall, especially with China eventually re-opening, then inflation could possibly rebound,” said John Vail, chief global strategist at Nikko Asset Management.

Investors are getting set for a rush of data next week, including minutes from the Fed’s latest meeting on Wednesday and the U.S. employment report for December on Friday.

Signs of continued economic strength could feed inflation fears and bolster the case for policymakers to keep rates higher for longer. Conversely, investors could read weakening data as a sign that a recession is approaching and head into bonds, a popular safe haven.

At the moment, the Treasury market “is more focused on inflation still than … recession,” said Matthew Miskin, co-chief investment strategist at John Hancock Investment Management.

“You need to have patience in the next couple of months, because if you get whipsawed out in this recent rise … and then you miss all the downside of yields, that would be the worst case scenario,” he said.

Matthew Nest, head of active global fixed income at State Street Global Advisors, believes yields will likely fall in 2023. Over the shorter term, however, their current upward trajectory could continue, pushing the 10-year yield to a test of 2022’s highs of around 4.25%, he said.

“The next big move will likely be down in yield,” he said. However, “you could experience some pain in the short run.”

(Reporting by Davide Barbuscia; Editing by Ira Iosebashvili and David Gregorio)

About the Author

Reuterscontributor

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest international multimedia news provider reaching more than one billion people every day. Reuters provides trusted business, financial, national, and international news to professionals via Thomson Reuters desktops, the world's media organizations, and directly to consumers at Reuters.com and via Reuters TV. Learn more about Thomson Reuters products:

Latest news and analysis

Advertisement